|

| Screen from the east |

Sandridge, a couple of miles north of St Albans, is one of those churches that has an outstanding headline act - in this case, a stone medieval chancel screen - but which turns out to have a fine supporting cast too.

There are plenty of stone screens in cathedrals and other major churches (such as abbeys), where they're called pulpita (singular, pulpitum), but there are only maybe a couple of dozen medieval examples in English parish churches, and Sandridge's is the only one in Hertfordshire.

|

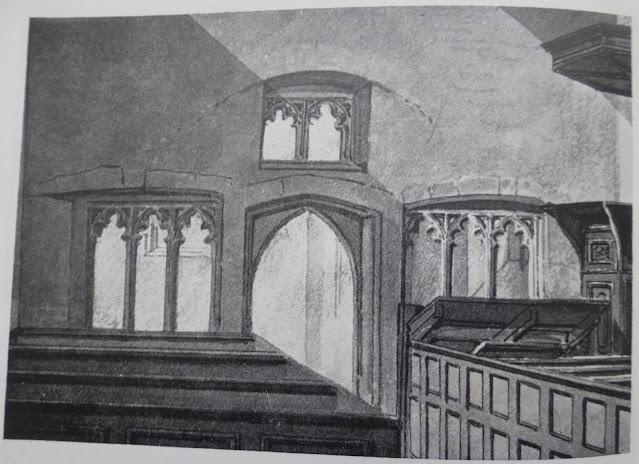

| Screen from the west; watercolour, J C Buckler, 1840 |

|

| Screen from the east; watercolour, J C Buckler, 1839 |

We know what the screen originally looked like thanks to J C Buckler, who painted numerous pictures of Hertfordshire churches in the 1830s and 40s and to which I often refer; they are now in the County Records Office in Hertford. It was constructed in the late 14th century, and the openings are Perpendicular in design, as would be expected from the date, but they are embellished with fleurons in the jambs, a feature more commonly associated with the Decorated style of earlier in the century. This embellishment is found only on the east-facing side, which is unusual as generally the side seen by the congregation rather than the clergy is the more elaborate of the two.

|

| Screen from the east |

This is only tangentially relevant, as he may not have ever set foot in Sandridge's church, but in researching for this post I came across Laurence Clarkson (1615-67), and I can't resist adding something about him. (He has a Wikipedia entry and one in the Dictionary of National Biography.*) He was the Baptist minister in Sandridge for about a year in 1646/7 before he was sacked for his unorthodox views. His fame (such as it is) rests on his having gone through six religions during his life (or, more accurately, six versions of Christianity). He was born into Anglicanism, then became a Presbyterian, an Independent, an Antinomian (as a Ranter), a Baptist, and finally a Muggletonian (all this against the background of the Civil War; he had joined Col. Fleetwood's regiment of the New Model Army). The shades of difference between these sects may be hard for us to grasp (or care much about) nearly four centuries later, but at the time they were argued and even fought over. He also, at various times, practiced astrology, healing and magic, rejected conventional morality, and was notorious for his libertinism.

He wrote one of the earliest English memoirs, The Lost Sheep Found, published in 1660 under the name Laurence Claxton, but unfortunately I can't recommend it as an enjoyable read: it concerns itself mostly with obscure theological disputes and self-justification (he particularly has it in for the Quakers), and the paragraphs are often many pages long. There are a few moments of unintentional comedy, as when in 1645 he was arrested and put on trial in Bury St Edmunds, during which the judge questions him with rather suspicious persistence about 'dipping' (baptising) naked women (which he denies having done). Occasionally he writes in a more anecdotal and lively style:

But now to return to my progress, I came for London again, to visit my old society; which then Mary Midleton of Chelsford, and Mrs Star was deeply in love with me, so having parted with Mrs Midleton, Mrs Star and I went up and down the countries as man and wife, spending our time in feasting and drinking, so that Taverns I called the house of God; and the Drawers [ie drawers of drink, the barmaids and barmen], Messengers; and Sack [fortified wine], Divinity; reading in Solomons writings it must be so, in that it made glad the heart of God; which before, and at that time, they improved their liberty, where Doctor Pagets maid stripped herself naked, and skipped among them, but being in a Cooks shop [well supplied with pleasures of the flesh], there was no hunger [desire/lust], so that I kept myself to Mrs Star, pleading the lawfulness of our doings as aforesaid, concluding with Solomon all was vanity. (pp28/9)

He became a Muggletonian in 1656. The sect was founded in 1651 by Lodowicke Muggleton; they were apolitical, pacifist and egalitarian, and believed, among other things, that God takes no interest in events on Earth and will not intervene until the Last Judgement. The last known meeting (they didn't hold services as such) of Muggletonians was as recently as 1940. Clarkson, however, died in Ludgate debtors' prison in 1667; he had fallen into debt because he lent £100 to some people to assist in the rebuilding of London after the Great Fire of 1666, and they absconded with it. An unfortunate end to a unusually full life.

* Anyone with a (free) UK library card will be able to access this; overseas readers will need a subscription.)

|

| Later medieval tiles |

No comments:

Post a Comment