On a recent visit to the excellent Higgins Museum and Art Gallery in Bedford I was struck by a new display of mosaic tiles excavated from the site of Warden Abbey. This wheel design, with its 'spokes' curved to make it look as if the whole thing is rotating anti-clockwise, a frozen Catherine wheel shooting clay shards in all directions, is especially intricate and appealing. It has six differently shaped elements, and must have required great ingenuity in designing and making it. There are a few traces of colour remaining, but mostly all that's left is the colour of the baked clay.

It's even more impressive seen in its original context. As you can see, the roundels - there were two of them - were merely small elements in a much grander overall scheme.

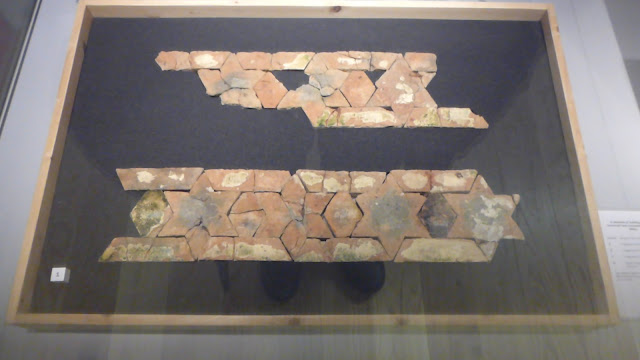

Also on display is this border, a frieze of six-pointed stars. Like the other mosaic tiles, they presumably date from c.1300 or a little later.

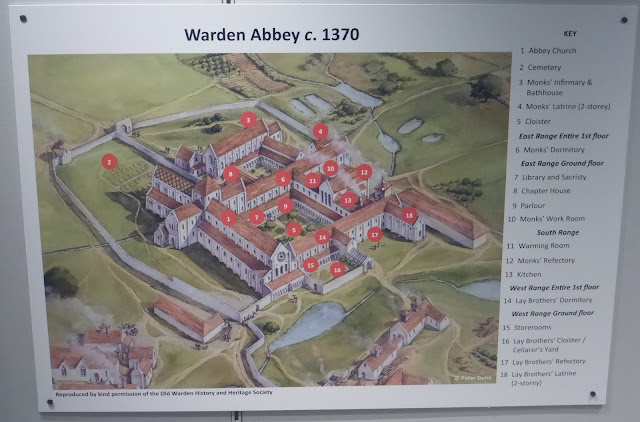

Warden Abbey (near the modern village of Old Warden, with its unparalleled collection of airworthy vintage planes) was founded in 1135 by Walter Espec, who'd also founded Rievaulx; they both belonged to the Cistercian Order of monks. Warden became one of the most influential monasteries in England, and had the largest abbey precinct of any in the country (143 acres). At its height, in c.1200, it had over 100 monks and 300 lay brothers (who worked in the fields and carried out other essential tasks).

Unfortunately the monk's overreached themselves in the late 13th century when they started an ambitious building plan, presumably including the elaborate (and therefore costly) tiles, and essentially went broke. External events such as the Great Famine of 1315-17 and the Black Death, which reached England in 1348, didn't help. The Abbey survived until the Dissolution (it was surrendered to the King's representatives in 1537), but its former prosperity never returned. Nothing now remains above ground, except some elements from the former Abbot's lodging which were incorporated into a mid-16th century house (now available for holiday lets via the Landmark Trust).

We might wonder why the Cistercians, who were famously ascetic when it came to the decoration of their buildings, allowed such extravagant designs on their floors. In 1205 the Abbot of Pontigny (France) was reprimanded for, among other things, allowing there to be an elaborate pavement in his church. He was told to remove it or change it so it no longer caused a scandal. Similarly, in 1210 the Abbot of Beaubec (France) got into trouble with the Order's authorities for allowing one of his monks to spend a long time making elaborate pavements. They were deemed to be the cause of 'levitas' (levity) and 'curiositas' (curiosity) in non-Cistercians, (presumably members of the Order were above such frivolity).

We don't know precisely what the offending tile pavements looked like. Reading between the lines of the various documents, it seems that the authorities objected to figural designs and bright colours. The Warden tiles are abstract and, although they've lost almost all whatever colour they once had, were presumably suitably modestly coloured, and so escaped censure.

I've written about mosaic tiles before, in Byland, Rievaulx and Ely, and Meesden.

Bibliography: Cistercian Art and Architecture in the British Isles, eds Christopher Norton and David Park, Cambridge, 1986.